This article contains spoilers for Past Lives.

In love, timing is pivotal. For the playwright turned first-time filmmaker Celine Song, the same holds true in the telling of a love story.

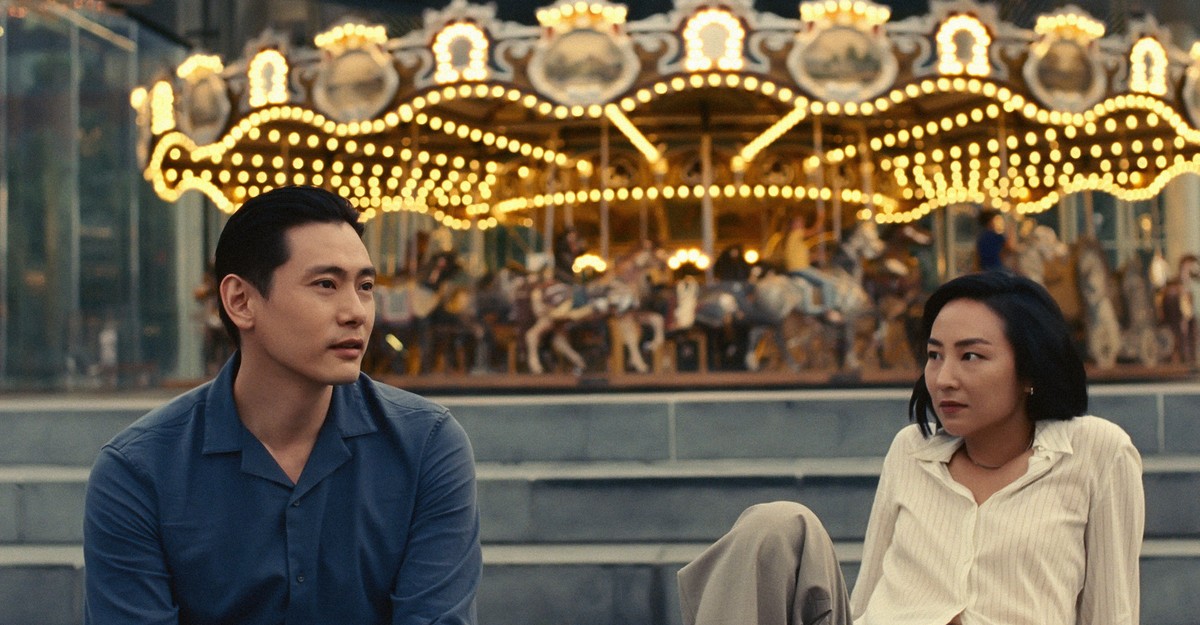

Song’s sweeping romance, Past Lives, spans decades and crosses continents as it depicts a woman reconnecting with her childhood sweetheart, but it deploys a delicate rhythm of absence, distance, and silence. The film—this year’s Sundance darling—follows Nora (played by Greta Lee) and Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), best friends in their youth who go their separate ways when Nora’s family moves from South Korea to Canada. They reconnect online as adults but fall out of touch again until Hae Sung visits Nora in New York, 24 years after the last time they saw each other in person. By then, she has a husband, Arthur (John Magaro)—and that’s the least of the changes in both of their lives.

Buoyed by a trifecta of fine-tuned performances, the movie sensitively tracks how Nora and Hae Sung have been shaped by their divergent paths, their connection tenuous yet precious still. It’s the kind of film that could have easily collapsed under the weight of its own sentimentality. Yet Past Lives is less about renewing a relationship than about exhuming it and dissecting the possibilities it once possessed. In both its pathos and its displays of affection, the film is assuredly told, largely because Song thought of herself as a conductor and her story as a composition. “I think every film is music, at its heart,” she told me when we met in Los Angeles last month. “The rhythm has to be perfect.” Her script is defined not just by the lines her actors deliver but by the deliberate silences between them, generating a pulse that expresses the ineffable. The result is a confident entry in the canon of great romances—one that expands the emotional scope of what a love story can be.

Past Lives opens at a bar, where Nora, Hae Sung, and Arthur have gathered for a drink. The audience doesn’t hear their conversation; instead, they listen to several onlookers who are watching the trio. These unseen commentators wonder how the two men are related to the woman seated in between. One suggests that Nora and Hae Sung are tourists, and Arthur “their American friend.” Another guesses that they’re colleagues. As the scene goes on, they point out how close the three of them seem and how they respond to one another—all while Song’s camera zooms slowly in on Nora. Song is holding the audience at arm’s length, intensifying the mystery. Perhaps you, too, started the sequence merely interested in how the characters know one another. By the end, you’re probably wondering how well they do.

Distance is key to the meditative magic of Past Lives. Song’s film is filled with space—the intangible kind between words, and the physical kind between characters. Often, Song frames Nora and Hae Sung facing each other, as if they’re approaching but never breaching, an invisible line dividing them. In one scene, on a subway car, Nora and Hae Sung’s hands rest on a pole an inch apart. The same effect lasts throughout the movie: Song’s characters always seem to stand apart just so, cued to speak just then—positioned perfectly in that zone of simultaneous intimacy and restraint. Yet the film never comes off as stiff. Such moments, taken together, produce the effect of a magnetic field emanating from Nora and Hae Sung, reshaping the time and space around them.

That said, Song never used a stopwatch or a tape measure to guide her. During Zoom meetings, she asked Yoo and Magaro to keep their cameras off so that they would organically act like strangers around each other on set. At in-person rehearsals, she made sure Lee and Yoo didn’t touch, so that creating personal space became second nature for the actors—and so, when they finally hug on-screen, the moment feels monumental. And Song let her internal clock guide a near-wordless scene in the final act, when Nora waits with Hae Sung for his Uber to arrive. She told me she wanted the sequence to convey that this farewell could be a final goodbye or one made just for now—“the highest of stakes and the littlest,” she said—so the time her characters spent standing on the curb had to “feel like it’s a little bit too long, but then also … like it’s too soon.” The resulting moment—with its aching, transfixing silence—captures Nora and Hae Sung’s potent mix of regret, relief, despair, and awe.

Song built Past Lives around the concept of in-yun, a Korean word that roughly translates to “fate.” She’d thought about it after experiencing what Nora does at the beginning of the film: Years ago, she found herself sandwiched between her white American husband and her Korean childhood sweetheart at a bar. The meeting inspired Song to write Past Lives; she left that evening musing about, she said, “how wild it is for me to be able to connect to both of these guys and … [for them] to get to know each other across language and across time.” That’s in-yun, she explained: a “passive” way to look at destiny. In-yun is not about “manifesting” or trying to will the future toward your desires; it’s about recognizing the layers of connections between everyone.

This notion is what unlocks Past Lives. Song’s film can be watched as a melancholy portrait of The One That Got Away, but seen through the lens of in-yun—which is illuminated by Song’s meticulous timing and staging—the movie becomes a bittersweet tale of loving and leaving behind one’s former self. Nora has obviously changed, and the version of her that Hae Sung knew is long gone. She’s a time capsule for Hae Sung, as he is for her. In each other, they get to visit and grieve who they once were.

Romance movies tend to follow an outline—boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back—with a twist. Maybe he’s gonna miss a plane. Maybe of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into his. Such films keep viewers enraptured by posing classic questions: Will they end up together? How?

Past Lives is more discreet, refusing to indulge its love-triangle setup by turning Arthur into a villain or Hae Sung into a saint. That’s why Song has Arthur imagine out loud “what a good story” Nora and Hae Sung would have if she fell for her old friend, and why Song tries to make clear that Hae Sung’s intentions were selfish: When he heads to New York, he’s freshly single, nostalgia fueling him to pursue closure. Besides, the Nora that Hae Sung loves is not the same one that Arthur does. A triangle never really existed.

What exists instead is a story that defies the many suppositions the onlookers in the opening scene—and, perhaps, the film’s audiences—make. “It is so easy to think about Who’s going to get the girl?” Song said. “If the characters do not see it that way, and they do not see it that way … hopefully the audience is also able to imagine that.” In the end, Past Lives imagines a transcendent, vulnerable form of love for Nora and the men in her life, one that can be platonic and romantic at once. What they all share is deep care and respect for one another, shaped by the maturity that comes with distance and time. “The truth is, I think that’s the amount of love that we all should be able to get,” Song said. If not in this life, the film suggests, then perhaps the next.

"Love" - Google News

June 06, 2023 at 01:50AM

https://ift.tt/VfbHO91

‘Past Lives’ Is a Love Story Timed to Perfection - The Atlantic

"Love" - Google News

https://ift.tt/C7OrWTA

https://ift.tt/NYCovRp

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "‘Past Lives’ Is a Love Story Timed to Perfection - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment