On Sunday night, a black female director could be awarded an Academy Award for the first time in Oscars history. In her new documentary Time, Garrett Bradley shares a poignant, decades-long story of one Louisiana family's struggle with the US prison system - through the lens of loved ones left behind.

In the first few minutes of Time, Sibil Fox Richardson looks straight down the lens and speaks to her husband Robert, then an inmate at the infamous Louisiana State Penitentiary.

"Do you see this smile, Robert?" Richardson whispers, beaming at the camera. "Do you know how hard I'm going to be smiling when you come home?"

In the clip, taken from a decades-old home video, Richardson's young face nearly fills the frame. She is resolute. "I feel like a champion," she says.

In the next shot, we see the same face, but aged, with grey hair at her temples. Richardson is nearing 50 and Robert has still not come home.

In September 1997, Richardson and her high school sweetheart Robert tried to rob a Louisiana bank. Newly married, the two had opened a hip-hop clothing store in Shreveport. But they struggled, becoming "desperate", Richardson tells us, with the store at risk of going under.

Richardson, who is now known as Fox Rich, accepted a plea bargain with a 13-year sentence and was released after three-and-a-half. Robert, advised by his lawyer not to take a plea deal, got 60 years without the possibility of parole.

Bradley's film does not dwell on the crime. She is more interested in the time that comes after. And rather than take us inside with Robert, Bradley trains her lens on those left behind. "It became really clear to me that there was a voice absent from the conversation around incarceration from a woman's point of view, from a family's point of view," Bradley said in a phone interview from her home in southern California.

Her film follows Rich in recent years as she fights for Robert's release, and pieces together the earlier years of his sentence with an archive of home video that shows her raising the couple's six sons.

The US prison system was "invisible by design", Bradley said. "In many cases the only evidence of what was happening is in those that are serving time on the outside."

Bradley, who is 35, was born and raised in New York City, the daughter of two visual artists. She studied religion at Smith College in Massachusetts before becoming a full-time filmmaker. Much of her work so far - including a handful of shorts and a fiction feature, Below Dreams - has explored the images of Black America that have been mostly left off screen.

Her 2017 short documentary, Alone, followed a young woman wrestling with whether she should marry her incarcerated boyfriend and started her focus on the prison system. Alone is the cinematic sister to Time, Bradley said, not least because it introduced her to Rich, who makes a brief but memorable appearance.

Bradley had originally intended Time to be a short film - matching Alone's running time at around 12 minutes. But on the last day of filming, Rich presented her with a bag filled with mini-DV tapes, totalling 100 hours of home videos.

The archival footage shows a young Rich talking thoughtfully to her absent husband and mugging for the camera. It shows the six boys riding bicycles, blowing out birthday candles, growing from toothless kindergarteners to college graduates - all while their mother waits for Robert to come home.

Bradley had already begun filming the short documentary in black and white when she was presented with Rich's old videos, which had been recorded in lush colour. She decided to convert the home footage to black and white to match. The colour scheme gave a "superficial sense of linearity", Bradley said. "The black and white sort of became the saran wrap over the whole film."

The result is a slow-paced film that slides quietly back and forward in time. Bradley forgoes any traditional signposting like on-screen dates or names. We estimate how much time has passed by the age of Rich's sons and the lines on her face.

The United States locks up more people per capita than any other country in the world, with some 2.1 million people in jails or prisons. Those behind bars are disproportionately Latino, Native American and African American. Black people are five times more likely than white people to be imprisoned. And the Rich family's home state of Louisiana has a higher rate of incarceration than anywhere else in the US.

Another film may have explored the details of the country's formidable prison system. Bradley's does not. There are no scenes shot from inside Angola, Louisiana's state penitentiary, no images of Robert in a prison jumpsuit. In the documentary we see the prison only from the sky.

When Bradley considered trying to explain US incarceration, she found herself "trying to explain racism in America", she told filmmaker Ava DuVernay.

What she gives us instead is more immediate, an 80-minute close up of one woman and her love story. Bradley's shots are intense and patient, often set against the swelling piano chords of Ethiopian composer - and nun - Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou. But Rich's voice and face dominate.

Before they began shooting, Rich and Robert told Bradley that they wanted their story to offer hope to other families affected by incarceration, Bradley said. And in front of Bradley's camera and her own, Rich is an almost unfailing picture of purpose and optimism.

"We start every year knowing that this is going to be the year my husband comes down," she says in the film. As each year goes by, she says, "Next year is the year."

Bradley seems to have made a conscious decision to show Rich the way she wants to be seen: powerful and sure. On phone calls with court clerks, desperate for information on Robert's pending release, she remains achingly polite while bounced from person to person, none of whom provide help. In just two scenes do we see her break. In one, Rich cries as she speaks of her twins. Not yet born when Robert was sentenced, their approaching 18th birthdays mark the length of his absence.

"I think there's a tendency for us to feel that one's vulnerability is somehow more true than their resilience and their strength," Bradley said. "As a filmmaker, I make the choice to lean into their strength."

After 21 years inside, Robert is finally released, his sentence commuted by Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards. In a film haunted by Robert's absence, his presence is almost implausible.

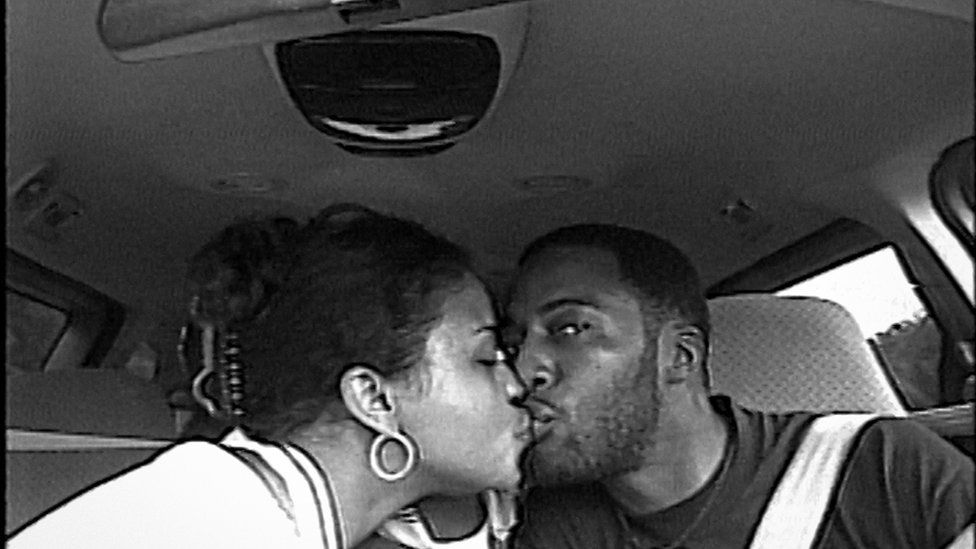

Their drive home together brings us one of the film's most poignant scenes - evidence of the close relationship developed between Bradley and Rich (described by Rich as "love at first sight"). Shot in slow motion by Nisa East, one of Bradley's cinematographers, we watch Rich and Robert, their clothes now removed, eyes locked, in a moment of intimacy in the backseat - and apparently unaware of the camera. For Rich, a woman so in control of her own image, it is only time in the film she forgets herself.

"I wanted to be with my love," Rich has said in interviews of her two decade fight for Robert. "There was nothing they could do or say that was going to stop me from putting my family together again."

In its final sequence, the documentary rewinds, playing a montage of home videos in reverse - the boys playing in backyard pools and bunk beds, a pregnancy and a birth. It runs all the way back to another kiss in another car between Robert and Rich from before the crime - showing both the time reclaimed and the time that was lost.

To Bradley, it was a sort of re-creation, an effort to match the images made in Robert's mind while he waited inside.

"It was something I wanted to give to Robert," she said.

All pictures copyright

"Love" - Google News

April 19, 2021 at 06:12AM

https://ift.tt/32sqP6O

Time: A love story coloured by incarceration - BBC News

"Love" - Google News

https://ift.tt/35xnZOr

https://ift.tt/2z10xgv

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Time: A love story coloured by incarceration - BBC News"

Post a Comment